Walmer Yard, W11

Conceptualising the House Museum

Walmer Yard’s Keeper Laura Mark recently took part in this event in partnership with The Mosaic Rooms and the Architecture Foundation in which she discussed Walmer Yard in the context of her research on house museums.

This conversation with artist Mahmoud Khaled and researcher Nadine Nour el Din, looks at ongoing research into house museums in London and in Cairo. Mahmoud focuses on his art practice which makes proposals for house museums while Nadine highlights the Mr. & Ms. Mohamed Mahmoud Khalil Museum in Cairo.

The Architecture of the Bed

On 19 July 2022, the renowned architectural historian Beatriz Colomina gave a talk at Walmer Yard which discussed how our bedroom spaces are evolving and how modern lifestyles and technologies have given the horizontal architecture of the bed a new significance. Followed by a discussion with architectural historian and curator Shumi Bose, it explored the new role of the bed as the epicenter of labour, post-labour and love in the age of social media.

Here we share a recording of that talk and discussion. Click on the image below to play the video.

The Architecture of the Bed

Tuesday 19 July, 6.30pm

The way we sleep and in turn the spaces we use for sleeping has evolved. In pre-industrial Europe, it was the norm to have two sleep cycles. The time to sleep was not decided by a specific time but by if there were things to do. People went to bed after dusk but would wake a few hours later for a couple of hours to read, do chores or have sex, before sleeping again until dawn. This pattern began to disappear during the late 17th century. With industrialisation came shift patterns and a more regimented approach to sleep brought about by the separation of home and the factory.

But in recent years this has again changed. Working from home, and even working from bed, has become the norm. In 2012, Wall Street Journal reported that 80 per cent of New York city professionals regularly worked from bed and as the pandemic means more of the population is working from home, the ability to have meetings in bed with those around the world has again shifted our relationship with the bed as a place to sleep.

There are many incidences of working from bed throughout history. Hugh Hefner famously never left his bed. His office moved into his bed in the Playboy mansion in the 1960s. His bed became the ultimate office with a fridge, hifi, telephone, filing cabinets, a bar, tv, video cameras, work surfaces and a bedside table. Truman Capote wrote from his bed. The architect Richard Neutra started working the moment he woke up with all the equipment needed for designing and writing in bed. And in his later years, Matisse would draw on his bedroom walls from his bed with charcoal affixed to a cane.

Bedrooms are one of the most personal spaces in our homes. They are also synonymous with sleep. But what happens when they become the host of many other activities?

In this lecture renowned architectural historian Beatriz Colomina will discuss how our bedroom spaces are evolving and how modern lifestyles and technologies have given the horizontal architecture of the bed a new significance. This lecture will explore the new role of the bed as the epicenter of labour, post-labour and love in the age of social media.

The talk will be followed by a discussion with architectural historian and curator Shumi Bose.

This lecture is held in partnership with The Mosaic Rooms.

About Beatriz Colomina

Beatriz Colomina is the Howard Crosby Butler Professor of the History of Architecture at Princeton University and the Founding Director of the Media and Modernity Program at Princeton University.

She writes and curates on questions of design, art, sexuality and media and her writings have been translated into more than 25 languages. Her books include Sexuality and Space (Princeton Architectural Press, 1992), Privacy and Publicity: Modern Architecture as Mass Media (MIT Press, 1994), Domesticity at War (MIT Press and Actar, 2007), Clip/Stamp/Fold: The Radical Architecture of Little Magazines 196X–197X (Actar, 2010), Manifesto Architecture: The Ghost of Mies (Sternberg, 2014) ,The Century of the Bed (Verlag fur Moderne Kunst, 2015) and Are We Human? Notes on an Archaeology of Design (Lars Muller, 2016). Her latest books are X-Ray Architecture (Lars Muller, 2019), and Radical Pedagogies (MIT Press, 2022).

She has curated a number of exhibitions including Clip/Stamp/Fold (2006-2013), Playboy Architecture (2012-2016), Radical Pedagogies (2014-2015), Liquid La Habana (2018), The 24/7 Bed (2018) and Sick Architecture (2022). In 2016 she was chief curator with Mark Wigley of the third Istanbul Design Biennial.

In 2018 she was mas made Honorary Doctor by the KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm and 2020 she was awarded the Ada Louise Huxtable Prize for her contributions to the field of architecture.

Back in 2018, Colomina hosted bed-ins at both the Venice Architecture Biennale and the Serpentine Pavilion, where she interviewed architects including Farshid Moussavi, Lesley Lokko and Sam Jacob in bed.

About Shumi Bose

Shumi Bose is an architectural historian, curator and educator. She is a Senior Lecturer in Architecture at UAL Central Saint Martins, and a visiting lecturer at the Royal College of Art. Shumi has worked as curator at the Royal Institute of British Architects and at the Venice Biennale; in 2021, she was appointed as a trustee of The Architecture Foundation and in 2020, founded Holdspace Architecture, a platform for architectural discourse outside of the academy. Shumi is interested in narratives of decolonisation and speculation, and likes to share stories from architectural education, publishing and curation.

The Big Sad Talk

Saturday 18 June 2022, 3pm

In partnership with London Contemporary Music Festival

Writing in Sad Boy Aesthetics (2021) Alex Mazey stated that melancholia is now ‘the fundamental passion of the hyperreal order’.

In this talk, held in partnership with London Contemporary Music Festival (LCMF) we will consider what we gain from relinquishment and ruination and how states of loss and exhaustion can enhance our creativity.

Join us for an afternoon panel discussion in Walmer Yard where we will explore Sad Boys, sweet melancholy and the affective turn with artist Rachel Rose, turntablist composer Mariam Rezaei, choreographer Marikiscrycrycry, author of Sad Boy Aesthetics Alex Mazey and LCMF artistic co-director Jack Sheen.

To RSVP email lcmf@lcmf.co.uk.

Empathy and Design: An Embodied Perspective

Wednesday 9 June 2021, 6.30pm

In this special guest lecture, the architect and professor Harry Francis Mallgrave will discuss human experience and how it influences architecture and the way we live.

Mallgrave’s work explores how newer models of the humanities and social sciences, together with technology, can help us to explore the nature of architectural experience in both its emotional and multimodal dimensions.

Setting this in the context of architectural theory, he will discuss the relationship between neuroscience and architecture and will reveal the neurological justification for some very timeless architectural ideas, from the multisensory nature of the architectural experience to the essential relationship of ambiguity and metaphor to creative thinking.

In this season of talks, neuroscientists, environmental psychologists, geographers, and anthropologists will talk about their work and how it relates to the field of architecture.

This series of talks will be taking place online via zoom. All participants will be sent a link to join ahead of the event.

Tickets are sold on a donation basis. All proceeds from the sale of tickets directly fund the work of the Baylight Foundation, which exists to deepen the public understanding of experiencing architecture through residencies at Walmer Yard and a cultural programme, as well as collaborations with artists, scientists, and other practitioners and organisations in arts and sciences.

About the speaker

Harry Francis Mallgrave is a Distinguished Professor Emeritus at Illinois Institute of Technology and an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects. He received his PhD in architecture from the University of Pennsylvania and has enjoyed a career as a scholar, translator, editor, and architect. In 1996 he won the Alice Davis Hitchcock Award from the Society of Architectural Historians for his intellectual biography of Gottfried Semper, and for more than fifteen years he served as the architecture editor of the Texts & Documents Series at the Getty Research Institute. He has published more than a dozen books on architectural history and theory, including three considering the relevance of the new humanistic and biological models for the practice of design. His most recent book, Building Paradise: Episodes in Paradisiacal Thinking, is currently in press with Routledge Publications. Drawing upon a theme first raised by Alvar Aalto, it offers both a selected history of the idea of paradise as well as a ‘garden ethic’ for the ecological practice of design.

Forum: Places of the Heart with Colin Ellard

Tuesday 4 May 2021, 6.30pm

Walmer Yard’s reading group, Forum, will launch its new season with the neuroscientist and author Colin Ellard.

Ellard’s book Places of the Heart: The Psychogeography of Everyday Life explores how our surroundings affect our thoughts, emotions and wellbeing.

From our experiences of ruins, to shopping centres or our own homes, Ellard’s writing looks at how these elements of urban design have influenced us throughout history, and how are brains and bodies respond to these different types of spaces.

The book investigates the influence new technologies will also have on our evolving cities, and what world we are, and should be, creating.

Ellard will be in conversation with Walmer Yard’s keeper Laura Mark, and this will be followed by an audience discussion.

In this season of talks, neuroscientists, environmental psychologists, geographers, and anthropologists will talk about their work and how it relates to the field of architecture.

This series of talks will be taking place online via zoom. All participants will be sent a link to join ahead of the event.

Tickets are sold on a donation basis. All proceeds from the sale of tickets directly fund the work of the Baylight Foundation, which exists to deepen the public understanding of experiencing architecture through residencies at Walmer Yard and a cultural programme, as well as collaborations with artists, scientists, and other practitioners and organisations in arts and sciences.

About the speaker

Colin Ellard is a neuroscientist, author and design consultant who works at the intersection of psychology and architectural and urban design. Ellard is a professor of psychology, specializing in cognitive neuroscience, at the University of Waterloo in Canada, where he also runs the Urban Realities Lab. After spending the early part of his career working on basic problems in visual neuroscience related to spatial function in animals, he later turned his attention to exploration of the human relationship with built settings. He is particularly interested in understanding the emotional effects of architecture, which he explores in both field settings and in synthetic environments using immersive virtual reality. Ellard’s current projects include exploration of the contribution of peripheral vision to architectural atmosphere, architectural contributions to the emotion of awe, and physiological stress in high-density urban environments.

Forum: The Life of Lines with Tim Ingold

Wednesday 12 May 2021, 6.30pm

In this edition of Walmer Yard’s reading group, Forum, the anthropologist Tim Ingold will discuss the ideas and concepts within his book The Life of Lines.

In The Life of Lines, Ingold argues that our world is woven from knots, and that this principle of knotting underlies both the way things join with one another, in walls, buildings, and bodies, and the composition of the knowledge embedded there.

His writings take in life, atmosphere, movement, surfaces, and what it means to be human from a perspective grounded in anthropology but weaving in interdisciplinary thoughts from the fields of philosophy, geography, sociology, art and architecture.

Ingold will give a short presentation, and this will be followed by a discussion led by Walmer Yard’s keeper Laura Mark.

In this season of talks, neuroscientists, environmental psychologists, geographers, and anthropologists will talk about their work and how it relates to the field of architecture.

This series of talks will be taking place online via zoom. All participants will be sent a link to join ahead of the event.

Tickets are sold on a donation basis. All proceeds from the sale of tickets directly fund the work of the Baylight Foundation, which exists to deepen the public understanding of experiencing architecture through residencies at Walmer Yard and a cultural programme, as well as collaborations with artists, scientists, and other practitioners and organisations in arts and sciences.

About the speaker

Tim Ingold is Professor Emeritus of Social Anthropology at the University of Aberdeen. He has carried out fieldwork among Saami and Finnish people in Lapland, and has written on environment, technology and social organisation in the circumpolar North, on animals in human society, and on human ecology and evolutionary theory. His more recent work explores environmental perception and skilled practice. Ingold’s current interests lie on the interface between anthropology, archaeology, art and architecture. His recent books include The Perception of the Environment (2000), Lines (2007), Being Alive (2011), Making (2013), The Life of Lines (2015), Anthropology and/as Education (2018), Anthropology: Why it Matters (2018) and Correspondences (2020).

Forum: The Aesthetic Brain with Anjan Chatterjee

Wednesday 2 June 2021, 6.30pm

In the third of our upcoming talks, Professor of Neurology, Psychology, and Architecture Anjan Chatterjee will take us on a journey through the beauty, pleasure and art.

His book, The Aesthetic Brain, uses neuroscience and psychology to explain why we are so concerned with aesthetics.

We’ll look at why we find art, buildings, and places beautiful and question what part our brain plays in deciding what we find aesthetically pleasing.

Chatterjee will give a short presentation, and this will be followed by a discussion led by Walmer Yard’s keeper Laura Mark.

In this season of talks, neuroscientists, environmental psychologists, geographers, and anthropologists will talk about their work and how it relates to the field of architecture.

This series of talks will be taking place online via zoom. All participants will be sent a link to join ahead of the event.

Tickets are sold on a donation basis. All proceeds from the sale of tickets directly fund the work of the Baylight Foundation, which exists to deepen the public understanding of experiencing architecture through residencies at Walmer Yard and a cultural programme, as well as collaborations with artists, scientists, and other practitioners and organisations in arts and sciences.

About the speaker

Anjan Chatterjee is Professor of Neurology, Psychology, and Architecture at the University of Pennsylvania and the founding director of the Penn Center for Neuroaesthetics. The past Chair of Neurology at Pennsylvania Hospital, Chatterjee’s clinical practice focuses on patients with cognitive disorders. His research addresses neuroaesthetics, spatial cognition, language, and neuroethics. He wrote The Aesthetic Brain: How we evolved to desire beauty and enjoy art and co-edited: Neuroethics in Practice: Mind, medicine, and society, The Roots of Cognitive Neuroscience: Behavioral neurology and neuropsychology and the forthcoming Brain, Beauty, and Art: Bringing neuroaesthetics into focus. He received the Norman Geschwind Prize in Behavioral and Cognitive Neurology by the American Academy of Neurology and the Rudolph Arnheim Prize for contributions to Psychology and the Arts by the American Psychological Association.

Open House 2020

Saturday 19 September, 11am – 5pm

We’ll be opening our doors to the public for the first time since February as part of next weekend’s Open House festival.

Join us to see inside House 1 of Peter Salter’s award-winning housing project. One of the largest houses on the site, House 1 displays many of the key features of the scheme and allows you to experience the rich textural qualities that the houses offer – from the reverberative black steel of the staircases to the softer clay and straw walls of the upstairs yurt.

Bring your own headphones and mobile phone to access our specially-created audio tour in which our Keeper Laura Mark describes the ideas behind the spaces and materials at Walmer Yard.

Please note: We will only be able to admit six visitors into the building at any one time and those waiting will be asked to form a socially-distanced queue on the street outside. When inside the house we ask that you wear a mask and stay 2m apart from other visitors wherever possible.

Open House 2020: Virtual Tour

Friday 18 September, 4pm

Walmer Yard’s Keeper Laura Mark will give a virtual tour of the houses and courtyard as part of Open House 2020.

Join the tour on our instagram @WalmerYard.

Dialogue: Lily Bernheimer

The fourth in a series of podcasts from Walmer Yard.

In this series we talk to those, often from fields outside of architecture, who are using different means to explore a deeper spatial understanding of the buildings which we inhabit.

In this episode we discuss how the spaces we inhabit shape our identities with the environmental psychology consultant, researcher and writer Lily Bernheimer.

Dialogue: Kate McLean

The third in a series of podcasts from Walmer Yard.

In this series we talk to those, often from fields outside of architecture, who are using different means to explore a deeper spatial understanding of the buildings which we inhabit.

In this episode we talk to the artist and graphic designer Kate McLean about her work recording the smells of cities through mapping and smell walks.

Learning from Japan (Part two)

Our last event before lockdown was a talk with the Japanese architect Akihisa Hirata and Walmer Yard’s architect Peter Salter. Both speakers discussed one of their own housing projects in relation to craft, materiality and the interpretation of home.

Here we share an edited transcript of Peter Salter’s discussion on his early work in Japan and how that led on to influence some of the ideas at Walmer Yard.

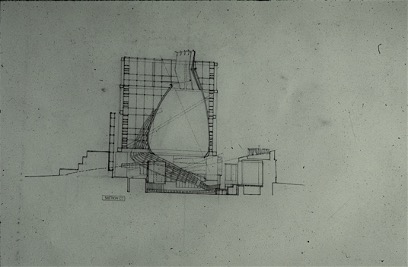

Peter Salter: Influences from Japan

The projects which I did in Japan were the result of Arata Isozaki and Alvin Boyarsky, who invited me to go there with my partner, Chris Macdonald. It is interesting because this was in 1990, and up until that point, not many architects went to Japan.

There was a whole earlier period of the Metabolists and Archigram but then there was a kind of gap. Isozaki came and asked Boyarksy, who was the head of the Architectural Association (AA) at the time, if he could recommend people to make a series of follies in Osaka. And so we were chosen, alongside Peter Wilson and all of the people basically teaching at the AA in those days, like Daniel Libeskind and Zaha Hadid and then some others from America.

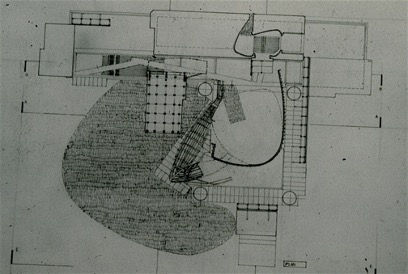

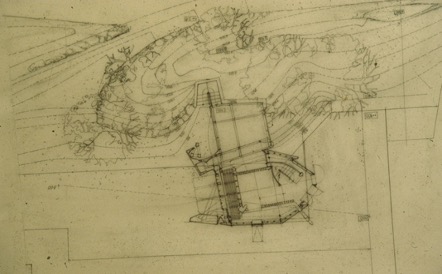

This is our folly for the Garden and Greenery Expo in Osaka.

The plan changed very often but basically in the end we made four lumps of earth. Those pieces of earth acted like bouys, which you navigated around.

In the end we couldn’t make the structure because it was cold moulded timber – a bit like the yurt structures on the top of Walmer Yard. There is a kind of family of forms that you use again and again. It was made of canvas held in form by a set of timber struts, which were done in the same way as a Japanese Minka house. There are very large pieces of structure, and then they are infilled with these smaller, finer pieces.

The main thing I want to talk about is the earth. When you go to Nara all of the precincts around Nara are made from rammed earth. They are constructed by putting a new layer of 75mm of rammed earth on the walls each year. Whereas we made ours in 19 days – it was very quick.

I’ll tell you about things we didn’t know about when we did our rammed earth. We ran out of clay, which is why there is all the striped clays. It was August in Japan so it rains a lot so we put a tile course in. The terrifying thing was the water content that came out of it. It sort of leached out of the rammed earth and as it did great lumps of earth came out too. So we were a bit desperate – we were worried it wasn’t going to last the Expo. Anyway, some wise person said don’t worry about it because gradually the water content will evaporate and the rate of erosion will go down.

The thing that’s nice about this project is that – which is really nothing to do with us – it was one of the coolest follies in the Expo because it had all this water leaching out of the earth. People went in there because in August it is really hot. So they would go in there with their umbrellas and stand and sit there cooling down.

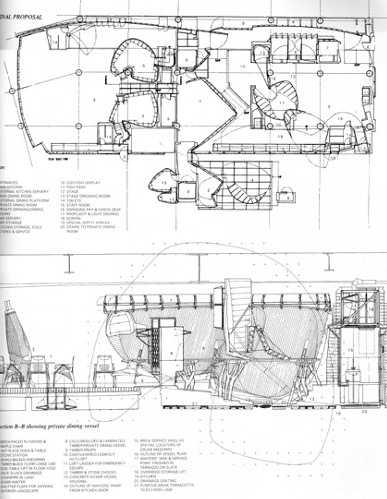

This is the Thai fish restaurant in Tokyo, which I did for Toyo Ito in 1995. He asked me to make a fish restaurant in one of the floors of what he told me was his first public building.

Once you entered there was a little pavilion and you went through right to the back of the site. There was a kind of bar and a place for more formal eating. Then if you really wanted to be expensive, you could hire a dining vessel, which you entered though a kind of folding staircase.

We were so constrained by the really deep beams and heavy structure. The columns were 1m in diameter – we were dealing with a really heavy structure because of earthquakes. So I used the notion of trying to clog up this space of all this structure with great lumps of timber.

From the windows you see there are two volcanoes. And all of the settlement was around the volcanoes – they weren’t active. This notion of the settlement from the volcano, and then the settlement around these lumps starts to come to play.

Akihisa Hirata talked about the space inbetween, and it is all about the space inbetween. You walk all the way through the thickness of the building, and then you arrive, and then life begins in a way. So it’s not quite the space inbetween but its certainly trying to work with the thickness and the length of the space.

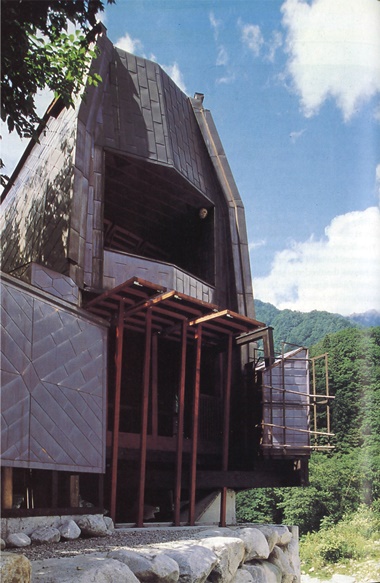

In 1995 we were invited to do another Expo – Expo Toyama. It was up in the skiing resorts of Japan. I made a building which is 30m tall, because it literally gets 12m of snow.

One of the things they do in Minka houses is they put up structures specifically for the snow so that you can walk in this inbetween space and the structure which has all the snow loaded onto it. So I used this notion of making a boat with the shells of the boat keeping the snow away. The pavilion is a boat and the snow is its water. Inside it you have a set of rooms – one of which you can see the peaks of Mount Tateyama.

Inside the Toyama Pavilion

The interior of a Minka house

Above is a picture from a Minka house which shows you the kind of very formal, very beautiful rooms and how they sit with the exposed structure above and it gets darker and darker. Then to the left is an image of the back of the shell and this is one of the rooms in the pavilion. You are literally walking in very dark circumstances in the space inbetween.

It was about how you arrived when you first saw the building and then when you got into the building, you had to move in a very determined way.

The other thing, which is very similar to the yurts at Walmer Yard, is that it was done with diamond copper tiles, because the structure is quite varied. The faceting is very soft, very gentle, like at Walmer Yard. In order to retain that faceting we used copper tiles as you couldn’t do it with straight standing seam copper. The tiles bent around the facets of the building.

I suppose my greatest influences are the Japanese Minka houses with their kind of delicacy and strength mixed together.

All of those projects were all about a kind of gloominess. Above is a picture of a bedroom in Venice. What is so beautiful about that picture is the light is just bending around the wall. And it’s working very softly with the bedspreads and the curtains. It’s just beautiful. I wanted to make all the rooms in Walmer Yard have a similar quality.

How the light gets into these rooms is quite important. Most of the light is from the top ranges of windows, which spreads light on the ceiling and the ceiling then reflects the light into the interior of the room.

In the Minka house, the floor defines the space. We step up into the kitchen area and then again onto the tatami matted floor. The whole thing about thresholds, which you’ll see at Walmer Yard, is very similar. You step up onto the floor and then you know that you have arrived.

This is my favourite bedroom at Walmer Yard. What is interesting about the Minka houses is the kind of patchwork of different clays and paper screens. I just think that it is so beautiful. So in Walmer Yard we try to make a patchwork of different materials. In the image below you get in-situ concrete, brown clay and white clay. We use the white clay sometimes to try and get more light into the room or to enliven a dark corner.

We remade a lot of silk kimonos to make these bedspreads. And you can imagine that if we had to have food on the floor that we would cover ourselves, our knees with these bedspreads.

The lacquered finish of the wardrobe doors

The steel of the bathrooms

The light across the clay walls

This is sprayed lacquered resin and in some instances you can’t tell the lacquer colour – which is an indigo colour – from the steel. Steel is black, the lacquer is blue and the two things start to merge and you can’t tell the form. These are curved forms just like the bathrooms are curved.

This is another Minka House. One of the Minka houses I went into where the person would pass through this little corridor space every day for 50 years. The clay had worn off and the colour had leached from it. I really like the idea of how the thing wears.

These are two images of the yurt upstairs, where you can see the chopped straw and how the light catches the chopped straw so that you get the darkness against the bright yellow strands.

We were always taught that when you looked at vernacular buildings, what you did is you took the principle but you didn’t take the image of it, but it’s really difficult not to get caught up with that.

Dialogue: Hirata and Salter was originally held at Walmer Yard on 21 February 2020.

Learning from Japan (Part one)

As we move more of our programming online, we thought we would revisit some of our past lectures, talks and discussions, that have taken place as part of our seasons on The Lesser Senses and Domesticity.

Our last event before lockdown was a talk with the Japanese architect Akihisa Hirata and Walmer Yard’s architect Peter Salter. Both speakers discussed one of their own housing projects in relation to craft, materiality and the interpretation of home.

Here we share an edited transcript of Akihisa Hirata’s lecture on his project Treeness House.

Akihisa Hirata: Japan-ness in Architecture

I’d like to begin with this picture, which shows a very ancient type of shrine beside Mount Fuji. In ancient times, there was no building – the void space is the shrine. The mountain is mystical, so the shrine doesn’t have to be a concrete building, but has to have some space to see the mountain. It shows the relationship between the natural and artificial in Japan.

This is a picture from my book, which shows the roof, and the picture below shows the mountain. I think they are very similar to each other as the roof is made to make the water flow on the surface and then the mountain is made by the flow of rainwater. So, in a sense this mountain is the same as the roof. An architect thinks that they are designing the roof, but actually, what they are doing is part of nature. If you look down from the sky, the activities of human beings, are almost like the activity of a microorganism on the surface of the ground. It is like part of the natural movement. Thinking about these similarities between the natural and artificial, is very key to Japanese culture and there are some specific words which relate to it and are very striking to me. One is Shakkei, which means borrowed scenery.

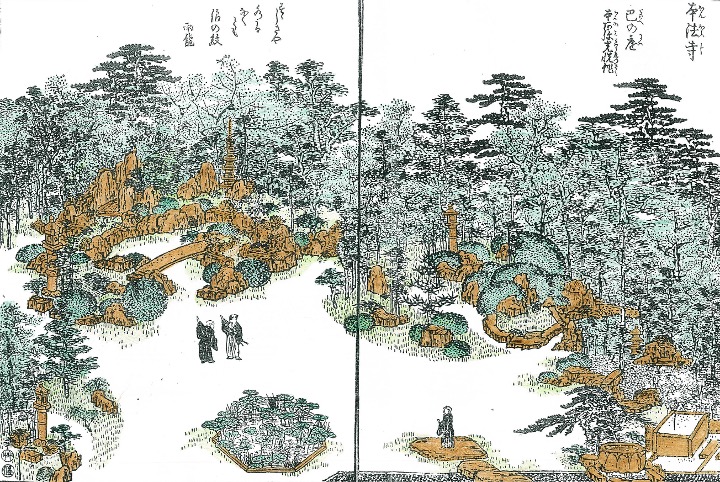

This is a photograph of the garden in the Entsuji temple, north of Kyoto designed by the ancient emperor Go-Mizuno. This garden is designed just to look at this mountain to the north of the city. It is very surprising because by making this view, the mountain – the natural thing – becomes almost artificial.

Another type of thinking about the Japanese garden is inclusive order. The image above shows the Honpouji Tomoe Garden designed by Koetsu Honami. I visited this temple with some of my students at Kyoto University with the garden designer and he showed us how he designed this type of garden. He recommend that we throw the colour on the drawing only on the part where there was existing stone and by doing this we could see the structure of the garden. Even if the plants were changed or replaced by another plant in 100 to 300 years, still this garden would be the garden by Honami because the configuration of the stone makes the garden original.

This type of structure is seen in many gardens in Japan. The photograph above is of the Saihoji Temple Garden designed by Muso-soseki. The structure of the garden is made by the pond and the stones. Most of the grounds will be changed over a long time span but the main structure of the garden will still be there.

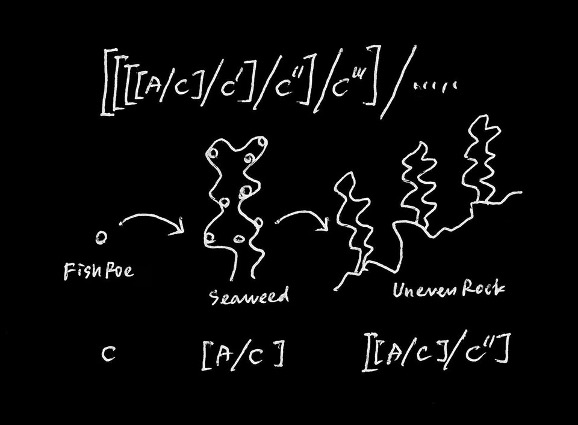

I think there are similarities between my architectural thinking and this Japanese garden thinking. The diagram above is from my book. It shows the fish roe tagging on the seaweed, and this seaweed is tagging on the ocean. There is a hierarchical system to this order. It is very architectural. Looking at this, it is almost like a rock in the garden and these smaller elements are like the plants or the moss of the garden. If we could use the structure of the architecture to make this type of order there would be an inclusiveness in the architecture. Making architecture is like making a garden.

The above photographs are of the typical Japanese teahouse – Joan, designed by Urakusai Oda. It shows the scale and savageness in the architecture of the Japanese tea house. It is very small – just 2m x 1m, with a height of 2.5m. But inside this small scale and limited space, we have many types of smaller scales and materials. And also, there are natural elements like trees and soil. So even though this tea house is sophisticated, there are elements which come from a savage situation. It makes the whole thing really interesting.

The main space is 2m x 2m and there is a fireplace where the master sits. There is a recessed space called the toko where decorative items are placed. People coming from the outside come through an entrance, which is called the nijiriguchi. This is really small – almost 1m lower in height and smaller than 1m x 1m. You have to crawl through it and it is like the visitor is being born when they enter.

Another example of Japanese space is the intermediate area between interior and exterior, which is sometimes called angawa. It is an inbetween space – between the inside tatami space and the outside garden space. It is a floor which connects these two elements. In my architecture, I dream of making something like this angawa space. In traditional Japanese architecture it is a very two dimensional space and I am trying to make an inbetween space which is three-dimensional – like butterflies flying inbetween branches or flowers.

So these butterflies are flying, enjoying this type of inbetweenness.

What I was trying to do in Treeness House was to make it as if the occupant is flying inbetween the flowers in a three-dimensional garden.

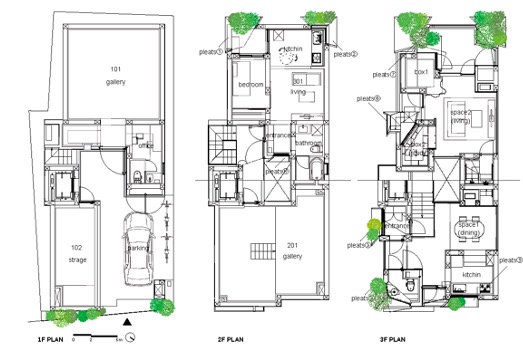

The word ‘Treeness’ comes from the three sides of the project – the trunk, then the branches and the leaves. I tried to combine these three different types of order in a hierarchical way and in a way suited to the urban situation.

This house and gallery is situated in the downtown area in Tokyo. The ground floor consists of rock-like elements which are boxy, concrete shapes. The gallery itself is a 6m x 6m x6m box that can be connected by a large door to the void space and the outside.

As you move up the floors of the building it gradually incorporates more natural elements with a mixture of inside and outside space.

The photograph above shows this mix of indoor and outdoor spaces. The dining room is in the front and then we see the living room in the distance but inbetween these two spaces there is a void which faces onto greenery. It is a bit similar to the scale of the teahouse where you can sit in an intimate way and spend time in a private space.

I was looking at the idea of using pleats in architecture and I adapted the pleated geometry to create the windows of Treeness House. There are 17 different types of pleated windows. They were made by using 9mm-thick steel panels welded together, and were made in a factory and then brought to site and connected to the concrete base.

The scenery of Tokyo has a flow of grand buildings and smaller buildings almost like a forest. I think it is really interesting that this three-dimensional house adds to the continuity of this scenery.

Dialogue: Hirata and Salter was originally held at Walmer Yard on 21 February 2020. Part two, which will be Peter Salter’s lecture, will be published later this week.

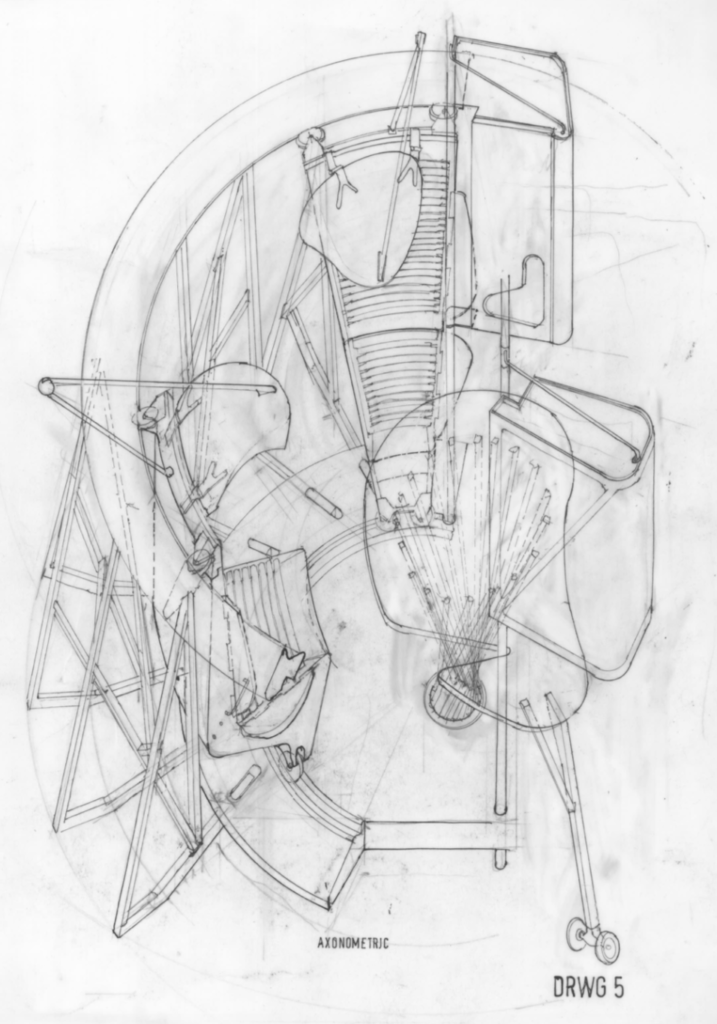

Revisiting Proposal B

In the week that the Venice Architecture Biennale would have been opening, we take a look at Proposal B by Peter Salter and Fenella Collingridge which was displayed in the Arsenale in 2018.

This intimate chair also speaks of a time post-pandemic when closeness was a possibility. It is designed with social interaction and courtship in mind.

The design takes form from a number of influences – the medieval ‘poche’ window seats of Stokesay Castle, a place from which to view the outside, away from the formalities of the aristocratic hearth, and the traditional kissing gate, which allows people, but not livestock to pass through.

Combining a table which moves on skateboard wheels, sliding lacquered chairs, felt blinkers and hoods, the moving parts encourage playfulness between two people.

As Peter Salter describes: ‘It acts in a similar way to the sofa in a living room, a place in which to ponder, argue or make-up, a centre of family conversation in the home.’

‘In Venice, the piece was always in use as a meeting place for people to celebrate a relationship, a place for selfies and smiles’, he adds.

The piece plays upon the spatial condition, where furniture becomes architecture and the ways in which we can manipulate space and with it the intimacy of a situation. The chairs’ occupiers can be brought together but also separated with a sweeping act of movement.

In Venice it challenged the normal social codes of conduct of an exhibition or gallery space, inviting you to touch, to sit, and to interact.

The curators of the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale, Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara of Grafton Architects, described it as ‘bringing to mind works by Jean Prouve, Pierre Chareau and the inventions, machines and drawings of Leonardo da Vinci’.

From the 317m-long, 21m-wide 16th century assembly hall of the Biennale’s Corderie to the 4m square space of House 2’s Media Room, where it temporarily resides, the chair now sits in a different scale of place and the intimacy becomes even more apparent.

Proposal B is a place for gossip and for chat, for sneaking a quick kiss, for the rub of a shoulder as the chairs come together. In a time when closeness, touch and intimacy are so challenged, relooking at this piece becomes increasingly poignant.

Credits

Design: Peter Salter and Fenella Collingridge

Construction: Daren Bye

Photography: Ste Murray and Jim Stephenson

Dialogue: LionHeart

The second in a series of podcasts from Walmer Yard.

In this series we talk to those, often from fields outside of architecture, who are using different means to explore a deeper spatial understanding of the buildings which we inhabit.

In this episode we talk to the poet LionHeart about his work recording emotional responses to architecture through poetry.

ZoomedIN Festival

Last week the Baylight Foundation and Walmer Yard’s Keeper Laura Mark curated a day of ZoomedIN Festival – a new virtual festival celebrating photography and architecture.

Our programme looked at how we experience the more sensual qualities of architecture when we can no longer visit it.

If you missed the events, you can now catch up with them on the festival’s Youtube channel or through the videos below.

One building, three takes

Walmer Yard is one of London’s most architecturally revered new buildings. It has been shot by a number of different photographers and although at first it seems instantly photogenic its developer Crispin Kelly has often remarked that it is difficult to get a photograph that really portrays the essence of the buildings and their internal spaces.

Our public programme is based on the experience of the buildings – either through visitors staying here or through events which explore a deeper connection to the architecture. In this talk we used photography and film to ask whether a building can truly be experienced without visiting it.

It included a screening of three short films/videos which portray Walmer Yard in very different ways followed by a discussion with those who have shot here on capturing the experience of the building in their work. Speakers included keeper of Walmer Yard Laura Mark, architectural photographers Hélène Binet and Jim Stephenson, and musician Haich Ber Na.

No Touching Please

How do we experience architecture when we can’t actually visit it? How do we express the sensual qualities of a space – be it through touch, sound or smell – when we are viewing a building via a screen?

As galleries, places of worship, museums, shopping centres, and other public spaces across the globe are closed, this discussion explored how the global pandemic will change how we visit buildings and spaces in the future and how we still capture the experiential nature of a space when we can’t collectively be there.

Speakers included Bompas and Parr founder Sam Bompas, Space Popular founders Lara Lesmes and Fredrik Hellberg, architectural visualiser David Deroo and photographer Ben Blossom, chaired by keeper of Walmer Yard, Laura Mark.

Dialogue: Simon James

The first in a series of podcasts from Walmer Yard.

In this series we talk to those, often from fields outside of architecture, who are using different means to explore a deeper spatial understanding of the buildings which we inhabit.

In this episode we talk to the sound artist Simon James about his work recording the hidden sounds of architecture.

Architecture for the senses

Today we are sharing a short film by architectural photographer and film maker Jim Stephenson, which explores the architecture of Walmer Yard.

The film focuses on the incredible light that passes through the houses at various times of the day, and of the wider sensory experience they offer.

It was first shown as part of Assemblage: The Lesser Senses, held at Walmer Yard on 26 October 2019.

'The personal encounter turns architecture into experience.'

Pallasmaa, Collingridge and Binet in conversation

As we move more of our programming online, we thought we would revisit some of our past lectures, talks and discussions, that have taken place as part of our seasons on The Lesser Senses and Domesticity.

The first is a discussion between the renowned author of Eyes of the Skin Juhani Pallasmaa, designer Fenella Collingridge and architectural photographer Hélène Binet.

The conversation, which was chaired by writer and curator Vicky Richardson, explored the role our senses play in the understanding of space, innocence in architecture and the framing of architectural imagery.

Read an edited transcript of the discussion below:

Vicky Richardson

Is it a more instinctive thing for you about feeling the atmosphere of the space?

Hélène Binet

Honestly, the first impressions for me are about walking, thinking, looking at how the light changes. It’s about putting together my emotion with what is the rationale. Architecture has a huge palette of expression, but I come from photography.

Vicky Richardson

Juhani, for a long time you have been thinking about and writing about architecture perhaps from a more unconscious or sensory side. Why is it so important for us to talk about this now?

Juhani Pallasmaa

My interest in sensory and sensual aspects of the world derive from my childhood as a farm boy. Nowadays when I am introduced as an architectural phenomenologist, I always feel a bit uneasy because my phenomenology is a farm boy’s phenomenology, which is concentrated on looking without preconceived theories and then trying to understand what I’m seeing.

It is only since I started to write I that I realised that the way phenomenological philosophies are defined is as pure looking. My eyes at the age of 83 are still a farm boy’s eyes. I look at phenomena with innocence.

I’m often introduced as a theorist, but I would object because I don’t even know what architectural theory could be. Architecture is much more a manner of personal expression than arising from theory. So, I’m confronting phenomena in the world and then reporting on what I see. I never theorise. It is always grounded on personal experience.

I have become really interested in architecture as experience. Only the personal encounter turns architecture into a poetic of architectural experience. I have been developing an understanding of architecture as experience fundamentally based on the great American pragmatist John Dewey who published the book Art as Experience.

Most architectural photographers photograph the building as an architectural object. As I understand it, Hélène photographs the building as her experience of it, which is a completely different thing.

Fenella Collingridge

There was one moment when she was photographing a window seat at Walmer Yard and she said ‘When I photograph a seat I sit in the seat to sit and then I get up and I take a step back and that’s when I take the picture.’ It was really lovely.

Vicky Richardson

I love what you said Juhani

about this idea of innocence and coming to architecture in an innocent way.Perhaps

the architecture world – of academia and professionalism – desensitises us. Maybe

we are over theorising and over rationalising what we see and experience. We

have to make some kind of relationship between the senses and the brain. How do

we do that without losing our innocence?

Fenella Collingridge

It is understanding the basic principles of how something is carrying loads or lit depending on what time of year it is – those interpretations aren’t really intellectual. They are almost intuitive. When you do make an intellectual interpretation, it is to do with organisational rigour.

Hélène Binet

I come from having to deal with translating the multi-sensory experience of a building into a visual experience. I see that from very early on humans had the necessity to frame the visual experience. Did the frame celebrate or kill the expression?

Juhani Pallasmaa

In my view architecture all around the world is in great trouble. This is for two reasons: it has already lost its innocence, both cultural and artistic, and it has turned into a kind of rhetoric instead of having an existential grounding. Architecture is fundamentally, as all arts are, about the world and human life within the world. It is not about architecture itself. Today’s architecture is dominantly about architecture as a discipline and a closed world. We are increasingly living in a scientific world which is detrimental to architecture. Architecture still has the task of bringing us back to myths and the unconscious world.

My favourite philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty, says: ‘we come not to see the work of art, we come to see the world according to the work.’ It is a beautiful formulation. This is the key in the loss of the relationship of architecture in our life world. It has become too much a professional, closed world.

Vicky Richardson

From very early on we have a drive to draw and to represent what we see. It happens in architecture as much as in art. For many centuries the idea of architecture carrying meaning has been very much part of the practice of architecture – even before we had architects.

Juhani Pallasmaa

I define architecture as a means of framing our view of the world and our existence in the world. Architecture does that at its best in a very humane and poetic manner.

We experience the world differently when experiencing it through architecture. Good architecture looks at the world for us. A good building, for instance, selects the aspects of the landscape and opens a window toward the mountain top or towards the apple tree in the garden.

Vicky Richardson

Architects have to go out and win arguments with clients and build things which answer a variety of requirements in a brief, often dealing with an extremely complex set of circumstances. Do architects need to rise above all that and do more?

Fenella Collingridge

At Walmer Yard we were gifted a good client, so it wasn’t such a big problem. If you really believe in what you are doing, then it is incredibly convincing to people. That sort of power usually enables you to win around the people who are sceptical or don’t want to do it that way or have a quicker, easier way. That goes right through from the client all the way through to the builders. That belief pulls everybody with you.

Lionheart (from the audience)

I am currently exploring the poetics of space and using poetry as an amalgamation of architecture to affect mental health. Juhani spoke a lot about ocular centres in Eyes of the Skin, is there ever going to be a time when we start centring emotions in space?

Juhani Pallasmaa

That has been my mission as a writer – to reveal our relationship with the world and how architecture rises from that relationship. I want to emphasise here that my background is as a practicing architect. I have one of the biggest architecture offices in Finland – I have 54 assistants. I am not speaking as a theorist at all.

‘Architecture needs two things – innocence and autonomy.’

Juhani Pallasmaa

Architecture needs two things – innocence and autonomy. Both of these are lost. The autonomy of architecture as an artistic expression is lost. We have become a service profession in most parts of the world. The architectural profession has to fight back its role as cultural agent instead of being connected with the business world.

From the audience

Is there a difference in the way that we experience and represent spaces that have been adapted from historic buildings or ruins and new build spaces?

Vicky Richardson

It makes me think of why it is that reused buildings make such great spaces for art and the role of memory in terms of the senses. Memory being intimately linked to our senses.

Fenella Collingridge

It is about things being worn, you can see how things were used, how the materials have aged. If you do something new, if you consider the grain of what you are building with then you get the same intimacy as something that has worn and weathered and carried a different set of memories.

Hélène Binet

Of course, to have a palette of materials which are both new and old is immediately rich, especially for composing an image. But it has to have a reason – that is what matters.

Juhani Pallasmaa

All architecture projects are contextual. They are always in dialogue with what exists. This is the same with renovation and with new buildings. The architect’s responsibility is to improve the human landscape. A responsible architect makes even a mediocre or bad piece of architecture look good.

Vicky Richardson

The contemporary interest in image seems to be heightened by the technology that we have access to now. It is like we are now incapable of making our own memories unless we can take a photograph of what we see. Is this the current thing because smartphones are relatively new or is this part of a wider urge, we have to document our lives?

Juhani Pallasmaa

There is a competition for architectural images. It is a completely wrong orientation. From its very beginning the art of architecture has been a relation of art. Buildings have related us with something else – cosmos. Relating us to the world, to other people and to other buildings, that has been the essence of architecture, but it has been lost in the competition for the image.

Hélène Binet

We almost don’t have enough distance to completely understand where we are going. My first wish would be to have a new name – that photography is one thing, and snapping is another. I don’t want to be moralistic about what is wrong and what is right, but I want to make a difference between the two.

There is nothing more important than time in experiencing an architecture of a landscape. This new tool doesn’t include time. What can we offer to recreate that thing? We still all biologically process our experience in the same way. We need to reintroduce time.

Vicky Richardson

To defend snapping, I’m a great fan of Instagram. I love seeing the fact that everybody photographs the same thing. This season the number of people I know who have been taking pictures of leaves on the pavement. Instagram is just full of leaves on the pavement. That is rather beautiful that we can create these kinds of connections.

Fenella Collingridge

Is it more beautiful than the leaves on the pavement though?

Juhani Pallasmaa

There is also a difference that many of the people who photograph the leaves on the pavement, don’t look at the leaves so much.

Vicky Richardson

There is looking, and then there is looking.

Takako Hasegawa (from the audience)

Coming back to emotions, could you talk more about choreographing emotions and how the space speaks to you emotionally. As a choreographer I think about how eyes travel, how the surfaces feel on the skin, and how spaces invite me to navigate. How does Walmer Yard speak to you in an emotional way?

Juhani Pallasmaa

Good architecture accompanies us. From the moment that you see the building it begins to have an effect on our behaviour. Architecture really takes us from one place to the other. Good architecture imagines on your behalf. When you have a desire to look out, the architect has placed a window right there. When you become interested in the floor above, a good building has the stair right there. It is a delicate choreography of human expectations and movements.

Fenella Collingridge

In this building – because the site is quite small to fit four houses on – a lot of the circulation is slightly extended, and you walk around something and through a shadow before you come to a room or a window. That gives a much more ritualistic and choreographed way of moving through it. Every time you enter a room you step up, which is an influence from Japan. Your body is registering these little increments.

Juhani Pallasmaa

That is one of the nicest details I have noticed during my stay here. You enter from the stairway on a concrete floor and then the wooden floor of the bedroom space is raised up. At the point of entry, you are in the world out there but when you take your shoes off and step on the wooden floor, then you are at home. It is a very good example of the subtlety of altering and conditioning our moves through the building.

Fenella Collingridge

The intimacy of people’s lives is so important in architecture and we often forget that.

Hélène Binet

I want to go back to the issue of perception because for me to do something, that is what I need – to feel the building on a different level.

I feel people have more of a horizontal or vertical perception of space. We want to feel the horizon. When we look and we move it is not always what we see but what also may be behind us.

Our experience of the horizontal is more significant. We have more sense of wanting to protect us from something which is around us.

Juhani Pallasmaa

The answer is very clear, good architecture prepares you for what is to come.

Architecture today has become so surface oriented that this emotional and experiential effect of what is behind a wall is somewhat lost.

Architecture is a totally plastic expression which doesn’t stop at the surface. Even in a room, good architecture maintains your consciousness of where you are. While you are in the intimacy of your room you are aware of the landscape and the city.

Architecture is an epic artform in the sense that it tells really deep and meaningful stories. Modern architecture in the last 20 years has lost this particular epic dimension – think of Alvar Aalto, Louis Kahn or Le Corbusier’s work, they are all epic works, like novels.

Crispin Kelly (from the audience)

Is the digital world of the future something which you feel will enhance our experience and connections in the world or do you feel it is a negative thing?

Juhani Pallasmaa

The digital world has made information more available but the important things, in the world and in life, are not information. That is the problem with the digital world – it tuns everything into information. It detaches it from its context and it detaches things particularly from the lived and emotive context.

So, although I would be a fool to say the digital world has no value – of course we wouldn’t have air traffic and up to date medical care without computers – but computers can be misused. They are much misused in architecture to replace human imagination particularly in architecture schools. Students should not be permitted to use computers in the first two years until they have passed a test which shows they have learned to imagine and feel through their imagination.

‘No technology is innocent.’

Juhani Pallasmaa

In today’s world we tend to think of all technologies as innocent. No technology is innocent. There is a study in Finland looking at kids around six to seven years old who have used digital technologies all their lives. They have lost their capacity to recognise human faces and to read human emotions. These are really serious things which are not thought about or talked about.

From the audience

Modern architectural photography often adds to the mythology of architecture through the image. What are the difficulties posed by architecture photography with or without people in it?

Hélène Binet

I am more interested in you entering the space which I have created in my photograph. You can then layer on to the image your own dream or perception or reference to something else. Not having a human figure in the image helps that process.

From the audience

When did we notice a change in architecture? Do we really agree that it is for the worse?

Juhani Pallasmaa

We are changing ourselves. One very important change is that we are increasingly becoming creatures of focused vision as compared to what we may have been tens of thousands of years ago. We ourselves are changing not only our architecture. We need to make a decision whether we wish to support these changes or fight against them.

Vicky Richardson

A lot of students are interested in the social engagement of architecture and the role of the architect as an activist. The desire to change the world through architecture is a very current concern and I wonder how this fits with the mission of architecture as an art form.

Fenella Collingridge

Social engagement is exactly an understanding of context and peripheral changes.

From the audience

Is the state of being able to stay innocent a privilege that not everyone is lucky enough to have?

Vicky Richardson

Is it a luxury to indulge our senses in architecture? Who has time for innocence?

Juhani Pallasmaa

I don’t see those two things as opposites at all. It is the innocence of poetry that opens up entirely new worlds for us.

From the audience

What is architecture?

Vicky Richardson

I recently read an essay by Susan Sontag called Against Interpretation which she wrote in 1964. She is calling the art forms to return to the senses and at the end of the piece she says: ‘we need to see more, feel more, hear more.’

What she is really saying is that we have become so reliant on interpreters in the arts. This is so relevant today. Not just in architecture but when I go to art galleries it feels like we are becoming ever more reliant on the text interpretation to guide us through the work and almost to tell us what to think. It is like we have lost out confidence to make a judgement.

It feels like we have decided there is a need to explain architecture, but we don’t do that with music. We don’t need to have the experience explained to us.

Hélène Binet

When you are at high school you learn the basic criteria for music, the history of art and literature, but not architecture. I have always wondered why. It is only a rare case that you are confronted with the complete set of tools to make architecture.

Juhani Pallasmaa

I teach around the world and usually when I begin a workshop, I start by telling my students: ‘I’m not even going to try to tell you what architecture is. I’m trying to make you understand who you are.’

Current education ignores the self, but the self is the ground of all understanding. We speak of architecture as something objective, but I believe architecture is more a matter of personal confession than anything rational or scientific. It is all about learning to understand who you are as the basic condition for creating architecture.

Dialogue: Pallasmaa, Collingridge and Binet was originally held at Walmer Yard on 26 November 2019 and was organised in collaboration with Architectural Design (AD) and in partnership with Arup.

Space and Sound: a workshop with Boonserm Premthada

Wednesday 18 March, 2 – 4pm

In this workshop, run in partnership with the Royal Academy of Arts, architect and founder of Bangkok Project Studio Boonserm Premthada will lead a workshop exploring the sounds of Walmer Yard.

Premthada received the 2019 Royal Academy Dorfman Award for his unique, deeply contextual approach to architecture. Many of his buildings consider sound equally important to light, shadow, wind, sound and smell – all elements he considers essential in creating architecture that serves to heighten its inhabitant’s awareness of their natural environments.

In this two-hour workshop Premthada will share his research gathered at sites around the world exploring how sound reacts with space.

Dialogue: Hirata, Salter & OMMX

Friday 21 February, 7pm

Japanese architect Akihisa Hirata will join the architect of Walmer Yard Peter Salter and the London-based practice OMMX for a discussion looking at how the architecture of Japan has influenced their work.

Each of the speakers will talk about one of their own housing projects in relation to craft, materiality and the interpretation of home.

Hirata’s futuristic Tree-ness House – a complex stack of concrete boxes containing living and gallery spaces – will contrast with the materiality and textures of Walmer Yard, which will be discussed by Salter.

The discussion will be chaired by Walmer Yard’s Keeper Laura Mark.

Assemblage: The Lesser Senses

Saturday 26 October, 1pm – 7pm

‘Assemblage: art that is made by assembling disparate elements – often everyday objects.’

Named an assemblage to reflect the gathering of many different speakers, participants and formats taking place during the day, this event will launch the new season at Walmer Yard and will take the form of a series of encounters and events held across the homes and centred around the theme of the Lesser Senses.

Following a key note presentation in Walmer Yard’s ‘coats-on lecture theatre’ by neuroscientist Danny Ball, a series of workshops, smaller talks, performances and film screenings will take place across the four houses, exploring how our senses affect our perception of architecture.

Guests will be encouraged to explore the homes throughout the afternoon while the interventions happen in tandem across the spaces. These include screenings of a new short film by Jim Stephenson on the sensory experience of Walmer Yard, a sound piece by Simon James, and spatial listening workshops led by Alex de Little.

Performances developed by designer and creative technologist Ava Aghakouchak will explore the synesthetic experience of Walmer Yard using an active wearable called ‘Sovar’. The tactile-visual amplifier aims to raise the wearer’s attention towards the more unnoticeable qualities of a space and help deepen their sense of presence within it.

Across the bedrooms Gonzalo Herrero Delicado, architecture curator at the Royal Academy of Arts, will host a series of conversations with artists, scientists and architects. While in the kitchens, conversations around the dinner tables with architects Alan Dunlop and Niall McLaughlin will discuss how we design for those with different sensory needs.

The day will conclude with a panel discussion and a drinks.

Sensory Walk

Saturday 2 November, 11am

Smell is rarely used to discuss architecture. Smells form part of our memories and our present engagement with spaces and surroundings but they are often elusive – disappearing before they can be described or pinned down.

Designer and researcher Kate McLean is one of a small but growing number of innovative practitioners dedicated to the study and capture of this highly nuanced field.

She will lead a sensory walk around Walmer Yard and the surrounding streets of Notting Hill.

Forum: The Idiot Brain

Tuesday 3 December, 7pm

Forum is Walmer Yard’s reading group. Each month a figure from the world of art, architecture, or science will choose a text which participants are encouraged to read. We will then join together to discuss the ideas and issues raised in the text over a glass of wine in one of the living rooms at Walmer Yard.

For this edition architect Ian Ritchie will select a text based around our second season’s theme of the Lesser Senses.

He will then join Walmer Yard’s Keeper Laura Mark in conversation as we open up the discussion around this critical reader.

His chosen text, The Idiot Brain by Dean Burnett, explores the brain’s imperfections and the impact these quirks have on our daily lives.

Neuroscientist Burnett, who also has a sideline as a stand-up comedian, tackles the brains effects on behaviour, memory, fear, intelligence and sociability.

Dialogue: Pallasmaa, Salter and Binet

Tuesday 26 November, 7pm

The renowned author of Eyes of the Skin Juhani Pallasmaa will join the architect of Walmer Yard Peter Salter and architectural photographer Hélène Binet for an unmissable discussion on the multi-sensory experience of architecture.

Using the architecture of Salter’s Walmer Yard as a backdrop for the discussion, the speakers, recognised for their architectural teaching and influential ideas and award-winning work, will use the theme of Walmer Yard’s second season – The Lesser Senses – to discuss the existential experience of architecture and its influence on our appreciation of spaces.

The discussion will be chaired by writer and curator Vicky Richardson.

Organised in collaboration with Architectural Design (AD) and in partnership with Arup.

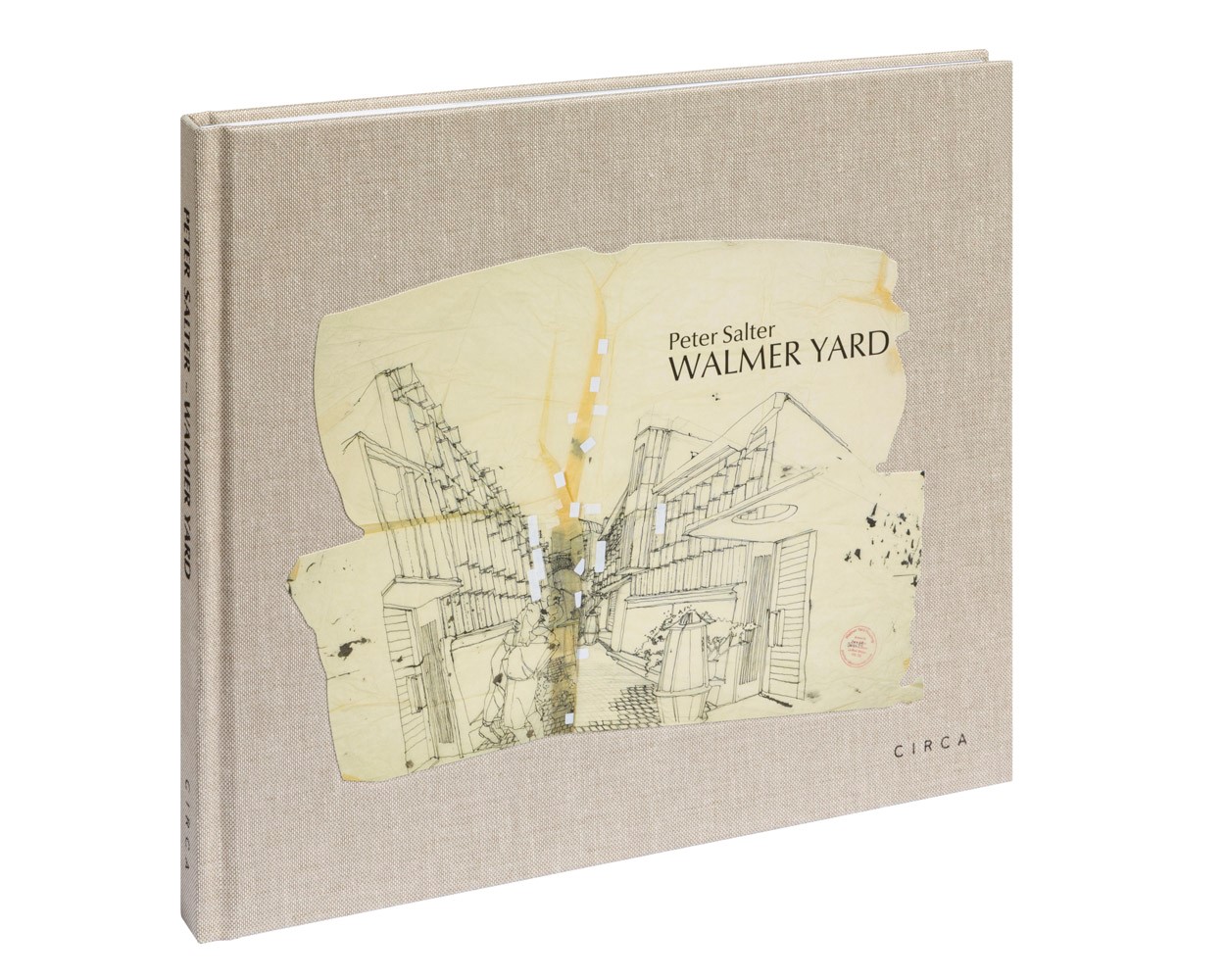

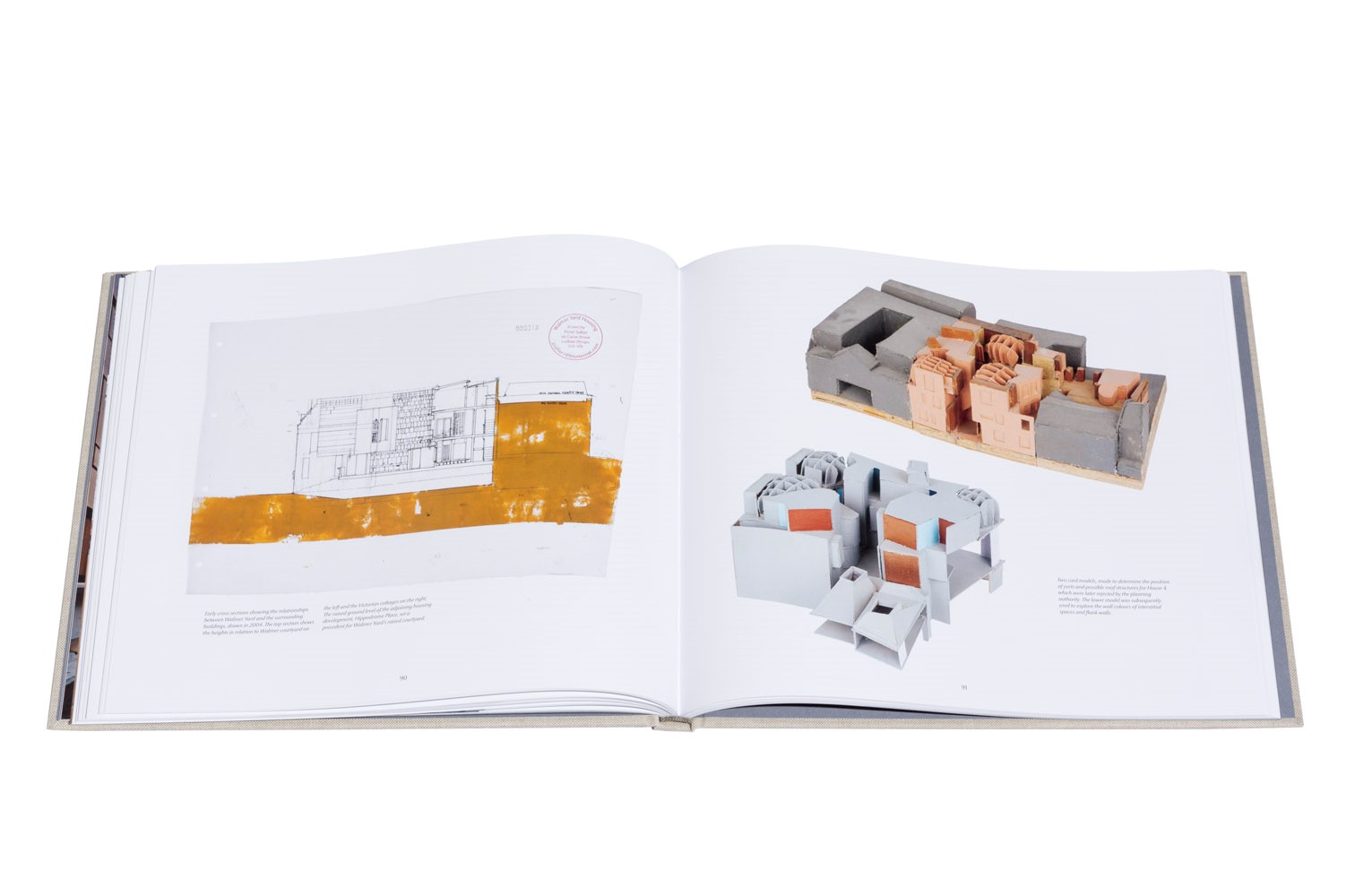

A new book on Walmer Yard

We have launched a new book on Walmer Yard which has just been published by Circa.

This book documents the evolution of the project through Peter Salter’s pen-and-ink drawings and Hélène Binet’s remarkable photographs combined with essays by key members of the team and others close to the project.

How we live together: a conversation with Fernanda Canales

Tuesday 14 May, 3 – 4pm

The meaning of domesticity can shift from person to person, but what happens when we compare the definition of home in contexts as different as Mexico and the UK?

In this conversation with Keeper of Walmer Yard Laura Mark, the Mexican architect and Royal Academy Dorfman Award finalist Fernanda Canales will explore topics of domesticity and housing through examples of her own work.

From projects such as Béstegui Housing (2019) to Bruma House (2017), her work focusses on the in-between spaces that are neither public nor private.

Canales will also reflect on the architecture and experiences of Walmer Yard within this context and take a closer look at whether an invitation to slow down and contemplate our surroundings is one of the answers to how we ought to live together.

Organised in partnership with the Royal Academy of Arts as part of the RA’s Architecture Awards Week.

Command Control Communicate

A curated experience by Visual Communication students from the Royal College of Art

Tuesday 7 May, 5pm – 9pm

We are constantly bombarded with signs, messages and orders; we are told not to cross the yellow line when a train is coming, not to step on the grass or touch an artwork, we are taught to follow rules. We abide by social values to create societal norms, utilise shame and punishment as a tool to discipline people who step out of line. We have been designed to conform. Everything around us, and within us, exists in a predetermined order. Nothing is new.

For their final show, students from the Royal College of Arts’ Design Without elective are conducting an experiment into the preoccupation of control in our lives and its unnoticed manifestations. Using one of the houses of Walmer Yard as the setting, the students aim to highlight and unsettle subconscious behavioural cycles through a journey of subversions and controlled simulations.

An interview with the Keeper

Our Keeper Laura Mark was interviewed by the Architects’ Journal about her new role at the houses and her plans for Walmer Yard.

Here is an excerpt from the interview:

Where have you come from and what is your role at Walmer Yard?

I was previously the architecture projects manager at the Royal Academy of Arts and before that I’d held many different roles at the AJ from intern to Architecture Editor. I’m now the keeper at Walmer Yard. It’s a slightly odd title which is more common in arts institutions where historically the keeper would be a curator looking after a specific area. At Walmer Yard I look after the building and its day-to-day running and I am also responsible for curating the public programme that will happen there and running the Baylight Foundation – the charity which is now based at Walmer Yard.

When did you start in the role and what have you been up to since you started?

I joined Walmer Yard in October and I’ve spent the last few months really getting to understand the spaces and working out what we might do in them. It’s been great getting to know the whole team, too, from Peter Salter to the contractor Daren Shaw and Fenella Collingridge, who worked with Peter on the design of the houses. Fenella is a real fount of knowledge on anything about Walmer Yard. Since I started I’ve been working on a book telling the story of the project from start to completion, giving tours of the buildings to architects and students, working on our public programme and developing the direction we will take all the things we do at Walmer Yard – from rentals to film location shoots.

What are you hoping to achieve?

It’s a unique place to work. It’s a real privilege to be given the opportunity to put my own stamp on what will happen at Walmer Yard and to be somewhere right from the beginning. I hope to develop an interesting programme which challenges the perception of architecture while opening up conversations about how we live and allowing the public to experience something different.

Supper Club: On Home

Thursday 4 April, 7pm – 10.30pm

The first in Walmer Yard and Natoora’s Supper Club series, this unique night will merge great food and quality produce in the architectural setting of Walmer Yard with conversations around domesticity and the home.

The first season of events at Walmer Yard takes a look at contemporary domesticity and how technology is changing our domestic behaviours. In a world where how we consume food is changing, where kitchens are becoming smaller, and we turn to apps like Deliveroo and UberEats for our food, this slow dinner will open up conversations about the future of how we eat in the home.

Natoora’s selection of produce will explore the seasonality of the food we eat as their growers guide guests through the intensity of end of season winter produce to the delicate flavours of new spring growth with a five course meal that captures the incredible flavour combinations that a slower approach to seasonality brings.

Assemblage: Exploring Domesticity

Saturday 27 April, 1pm – 7pm

‘Assemblage: art that is made by assembling disparate elements – often everyday objects.’

Named an assemblage to reflect the gathering of many different speakers, participants and formats taking place during the day, this event will launch the public programme at Walmer Yard and will take the form of a series of encounters and events held across the homes and centred around the theme of Domesticity.

Following a key note presentation in Walmer Yard’s ‘coats-on lecture theatre’ by Shumi Bose, a series of workshops, smaller talks and film screenings will take place across the four houses, tackling the juxtaposition of the absence of technology in Walmer Yard with the current increasing presence of technology in our domestic environments.

Guests will be encouraged to explore the homes throughout the afternoon while the interventions happen in tandem across the spaces.

In the living room, the Feminist Internet will host a workshop exploring the gender stereotypes created by personal intelligent assistants like Siri, Alexa and Cortana and the implications this has on the design of our homes and domesticity.

Across the bedrooms Gonzalo Herrero Delicado, architecture curator at the Royal Academy of Arts, will host a series of conversations addressing the use of technology in the home. These will also explore the means in which we communicate with those who we live or share our domestic spaces with. From the bed Gonzalo will conduct conversations with speakers not just in the same room but also located in New York and Spain. Those joining Gonzalo ‘in bed’ include architecture practice Space Popular, curator of the Design Museum’s latest show Home Futures Eszter Steierhoffer, and artists Fru*Fru.

In the kitchen Bompas and Parr will lead an exciting workshop reimagining the future of the napkin.

Conversations around the dinner tables will discuss how we use our kitchens, what the meaning of home means to those who have been displaced, houses as a place of work, and the changing nature of the private, social and romantic spaces of the home.

While in the media room showings of Ila Beka and Louise Lemoine’s Koolhaas Houselife will explore the daily life of the housekeeper and those responsible for looking after Maison à Bordeaux, designed by OMA in 1998.

The day will conclude with a panel discussion and a drinks reception to celebrate the launch of the Baylight Foundation at Walmer Yard.

Supper Club: On Craft

Thursday 9 May, 7pm – 10.30pm

‘The craftsman’s tools are not sentimental trinkets or charms, but honed pieces of equipment that enable the craftsman to reproduce detail with precision.’

We often pass over the everyday aspects of our lives, taking for granted where we live and how we eat. Step inside Walmer Yard for a supper of seasonal produce, and learn to recognise the craftsmanship that goes into creating both food and home.

Co-hosted by Natoora Founder Franco Fubini and designer of Walmer Yard Fenella Collingridge, this unique supper will draw connections between the genuine artistry of growing exceptional fruit and vegetables and the decade of design choices that have made Walmer Yard a uniquely crafted home.

Part of London Craft Week 2019.

Forum: The Grand Domestic Revolution

Thursday 23 May, 7pm – 9pm

Forum is Walmer Yard’s new reading group. Each month a figure from the world of art, architecture, or science will choose a text which participants are encouraged to read. We will then join together to discuss the ideas and issues raised in the text over a glass of wine in one of the living rooms at Walmer Yard.

The first event in this series will see architectural historian and broadcaster Tom Dyckhoff select a text based around our inaugural season’s theme of Domesticity.

He will then join Walmer Yard’s Keeper Laura Mark in conversation as we open up the discussion around this critical reader.

His chosen text, The Grand Domestic Revolution by Dolores Hayden, looks at the history of feminist designs for American homes, neighbourhoods and cities.

The eponymous 1982 publication, looks at the work of a group of American feminists including Melusina Fay Peirce, Mary Livermore, and Charlotte Perkins Gilman, who campaigned against women’s isolation in the home and confinement to domestic life as the basic cause of their unequal position in society.

In looking at this group’s plans to transform American neighbourhoods through communal kitchens, housewives’ co-operatives and new building types, Hayden brings to light the economic and spatial contradictions which outdated forms of housing and inadequate community services create for women and for their families.

‘This is a book that is full of things I have never seen before, and full of new things to say about things I thought I knew well. It is a book about houses and about culture and about how each affects the other, and it must stand as one of the major works on the history of modern housing.’

– Paul Goldberger, The New York Times Book Review

The Modern House at Walmer Yard

Last week The Modern House came to stay at Walmer Yard for the latest instalment in their Field Work series.

Read what they thought about their time in our ‘intriguing’ and ‘complex’ houses.